When most of us think of espresso, we imagine dark crema, bold flavor, and a shot of energy. But what if your espresso is also a microscopic universe?

Based on research by Pascal Bertsch, Abinaya Subramaniyan, Chahan Yeretzian, and Stefan Salentinig from University of Fribourg and the Coffee Excellence Center of ZHAW (Zurich University of Applied Sciences).

Click to read a full paper — open access.

A new study by four scientists reveals that espresso is far more than hot water passing through ground beans. Structure matter and gives the espresso its unique properties! It’s organized in complex mix of invisible structures—tiny oil droplets, long sugar-protein chains, particles, and gas bubbles like a nanoscopic material—all working together to give espresso its body, color, mouthfeel, and flavor.

And here’s the good news: this study is open for everyone to read, not hidden behind paywalls. Knowledge like this belongs to all of us—farmers, roasters, baristas, and everyday coffee drinkers. Thanks to Pascal Bertsch, Abinaya Subramaniyan, Chahan Yeretzian, and Stefan Salentinig - let's support they work.

Espresso: A Drink Made of Structures, Not Just Flavor

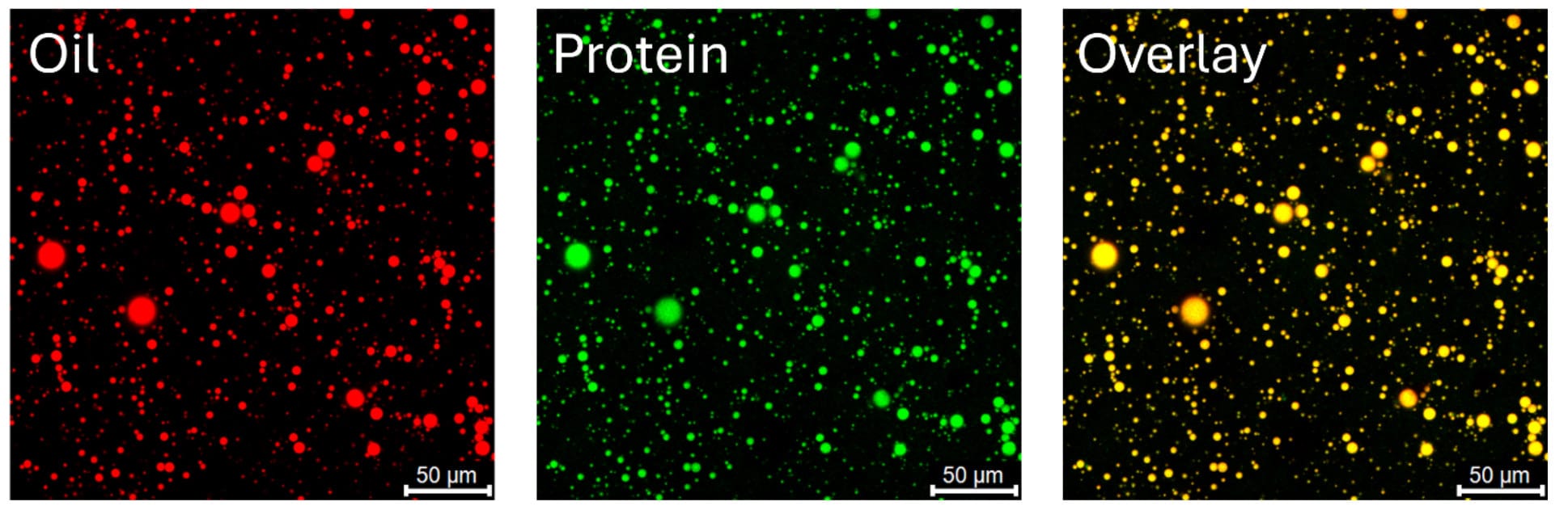

Espresso isn’t just about taste compounds like chocolate notes or floral hints. It’s also about structure. Scientists call it a colloidal system—a fancy way of saying it’s a drink where tiny oil droplets, water, sugars, proteins, and gas live together in balance.

Here’s what’s inside:

- Oil droplets: These carry many of espresso’s strongest aromas. They’re incredibly small—smaller than bacteria.

- Polymers: Long molecules made of sugars and proteins. Think of them like microscopic spaghetti strands, tangling and thickening the liquid.

- Melanoidins: Brown-colored giants formed in roasting. They give depth, bitterness, color and help stabilize the mix.

- Crema bubbles: CO₂ trapped in foam, held together by proteins.

Together, these parts create the creamy texture and “weight” we describe as body. Body is not just TDS (total dissolved solid), it’s the way all is organized. Espresso is an material, not just dissolved ions, that define among others the sensory “mouthfeel” and “body.”

The First Drops Matter Most

The researchers brewed espresso from Rwandan Arabica coffee using a home-style espresso machine. But instead of drinking it straight, they divided each shot into three parts: the first 12 milliliters, the middle, and the last.

What they found is striking:

- The first drops of espresso are the richest. They contain the most and largest oil droplets, the most tangled polymers, and the thickest texture. They have by far the highest mouthfeel.

- Later parts of the shot get thinner. The droplets shrink in size, the polymers untangle, and the liquid behaves more like plain water with dissolved ions.

In practical terms: if you’ve ever noticed that a ristretto (short shot) tastes denser and heavier than a lungo (long shot), this study explains why. The nano-structure that create creaminess are front-loaded in the extraction.

Why Espresso Feels Creamy

One test measured how espresso flows. Scientists pushed and pulled on the liquid, looking for signs of “elasticity.” The early fraction of espresso—the first few drops—behaved like a weak gel. It stretched and bounced back, thanks to those tangled polymers. By the end of the shot, that gel-like quality was gone, leaving a liquid that flowed just like water.

Translation: when you sip an espresso and feel it coat your tongue, you’re experiencing the work of invisible polymers and oil droplets teaming up.

What This Means for Coffee People

(My perspective, based on the research and my own experience in coffee)

The study doesn’t give brewing advice — it focuses on measuring what’s inside espresso. But looking at the results through the lens of barista practice, roasting, and farming, here’s what I see:

- For baristas: If you’re chasing rich, syrupy body, pay attention to shot yield. A shorter shot locks in the early fraction, where the structures are strongest. A longer shot dilutes that effect.

- For roasters: Roasting creates melanoidins and changes how polymers extract. Roast style may shift how “nano-structures” forms and how much ends up in the cup.

- For farmers: The cell walls of coffee beans contain the raw materials—polysaccharides—that later become these polymers in espresso. How beans are processed and dried can influence how they extract.

- For everyday drinkers: When you enjoy a shot with velvety mouthfeel, you’re not just tasting coffee—you’re feeling the dance of nano-structures on your tongue.

Crema: Not Just Pretty Foam

The golden foam on top of espresso isn’t just decoration. Crema is made of CO₂ bubbles, stabilized by the same proteins and melanoidins that support the drink below. When it collapses quickly, it means those stabilizers at the surface of the air bubbles are weaker. While crema doesn’t equal “quality,” it’s part of the same story of structure.

Why Open Science Matters

This paper is not behind a paywall—it’s free to read and share. That matters. Too often, coffee science stays locked in universities, or only reaches those who can afford expensive courses. But espresso belongs to everyone—from a farmer in Rwanda to a barista in Paris to a customer in New York.

By making the science open, the authors show respect for the global coffee community.

Support this work

If this text was useful to you, you can support Red Ink Coffee.

Contributions help cover basic infrastructure costs and keep this space independent.

Voluntary. No perks. No obligations.