Stenophylla: A coffee for the future?

- Krzysztof Blinkiewicz

- Aug 5, 2025

- 9 min read

Coffea stenophylla has the potential to help coffee plants survive; however, it is itself threatened with extinction.

Introduction

Climate change is one of the most pressing challenges faced by the coffee industry today. Rising temperatures, extreme weather events, and the spread of pests and diseases threaten the cultivation of Coffea arabica and Coffea canephora (robusta), the two most widely grown coffee species. While Robusta exhibits higher resistance to heat and disease, it often falls short of Arabica in terms of cup quality. Consequently, researchers are actively searching for alternative coffee species that offer both resilience and high-quality flavor.

One particularly promising candidate is Coffea stenophylla, a rare coffee species with unique attributes. Not only does stenophylla tolerate higher temperatures than Arabica, but it has also demonstrated a sensory profile remarkably similar to high-quality Arabica coffees. Its "rediscovered" only few years ago. However, this species remains critically endangered, with wild populations at risk due to deforestation, climate change, and agricultural expansion.

Could stenophylla be the key to the future of coffee? Let's delve into its history, genetic and chemical composition, sensory characteristics, and conservation efforts to explore its role in the evolving coffee landscape.

Diversity in the Coffea Genus and the Need for New Cultivars

The Coffea genus comprises approximately 130 species, most of which are not commercially cultivated. Many of these species contain caffeine, though some, such as Coffea charrieriana, are naturally caffeine-free. One distinguishing feature of Coffea plants is the presence of domatia—small indentations on the lower side of leaves that may serve as microhabitats for beneficial mites. These features, along with leaf shape, size, and fruit characteristics, help taxonomists differentiate coffee species.

Arabica coffee (Coffea arabica) is a naturally occurring hybrid of C. canephora and C. eugenioides, making it an allotetraploid (2n = 4x = 44). This means that all cultivated Arabica plants trace back to a single hybridization event, resulting in a narrow genetic base. Consequently, Arabica is highly susceptible to pests, diseases, and climate stress. Furthermore, the majority of its cultivated varieties belong to the Typica or Bourbon lineages. Long-term selective breeding, combined with Arabica’s tendency for self-pollination, has further reduced genetic variability, limiting its adaptability to changing environmental conditions.

Several wild Coffea species are now being explored for their potential to improve coffee resilience and keep a high sensory quality of flavor. These include:

Coffea stenophylla

C. racemosa

C. dewevrei (Excelsa)

C. eugenioides

C. congensis

C. liberica

C. namarokensis

C. brevipes

C. ambongensis

C. zanguebariae

Each of these species offers unique traits that could contribute to breeding programs aimed at increasing resistance to climate-related stressors. Among them, Coffea stenophylla stands out for its combination of heat tolerance and Arabica-like flavor profile.

Botanical Characteristics and Growing Conditions of Coffea stenophylla

C. stenophylla differs significantly from Arabica both genetically and morphologically. Unlike the red or yellow cherries of Arabica, stenophylla produces black fruit, resembling blackcurrants. However, its green coffee beans are similar in size and color to Arabica.

More importantly, C. stenophylla thrives in environmental conditions that are entirely different from those suited to Arabica, which contributes to its potential for a sustainable future. While Arabica—using native populations in Sudan and Ethiopia as a benchmark—flourishes at elevations of 1,000–2,200 meters above sea level (masl), C. stenophylla is native to the lowland forests of Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Côte d’Ivoire, where it grows at just 400 masl. This species also exhibits significantly greater heat tolerance than Arabica, thriving at an average annual temperature of 25–26°C—up to 6.8°C higher than Arabica’s optimal range of ~18.7°C. Additionally, C. stenophylla requires annual rainfall between ~1,500 and 2,288 mm, slightly exceeding Arabica’s ~1,600 mm requirement.

These characteristics suggest that C. stenophylla could be cultivated in regions where neither Arabica nor even Canephora can thrive, potentially expanding the global coffee cultivation belt. Furthermore, its heat tolerance may enable it to withstand rising global temperatures driven by climate change, making it a promising candidate for future coffee production.

Genetic Insights and Chemical Composition

A deeper genetic analysis of C. stenophylla reveals important insights into its evolutionary lineage and potential hybridization opportunities. Recent research using genotyping-by-sequencing (GBS) has unveiled the genetic diversity of stenophylla populations in Sierra Leone, highlighting bottlenecks in its historical population. Studies suggest that despite its limited genetic pool, stenophylla maintains high adaptability traits, making it a viable candidate for breeding programs.

A key determinant of coffee flavor is its chemical composition. Green coffee contains up to 700 different chemical compounds, all of which influence the final taste of roasted and brewed coffee. A team of scientists, including the renowned coffee botanist Aaron P. Davis, employed liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS) and metabolomics (PCA) to analyze and compare the green bean chemistry of C. stenophylla, Arabica, and Robusta. Using 26 samples for a highly representative comparison, their study focused on several key compounds that shape coffee’s sensory attributes:

Organic Acids (Influencing Acidity and Fruitiness)

Stenophylla has:

Lower quinic acid and malic acid levels than Arabica, which may contribute to differences in perceived acidity and fruitiness.

Similar citric acid content to Arabica, reinforcing its comparable flavor profile.

As is well known, the citric acid content is more important for the fruity character of the coffee, as it is the only one above the detection threshold.

Chlorogenic Acids and trigonelline (Bitterness and Antioxidants)

Chlorogenic acid and trigonelline levels in stenophylla are similar to Arabica, suggesting that its bitterness after roasting is closer to Arabica than robusta.

Sucrose (Sweetness and Caramelization)

Stenophylla has a higher sucrose content than robusta and similar levels to Arabica. This is significant because sucrose contributes to the development of caramelized and sweet flavors during roasting. Remember that sucrose is the precursor of various roasting products, including organic acids such as formic, acetic and lactic acid.

Alkaloids (Caffeine and Theacrine)

C. stenophylla has a caffeine content comparable to Arabica, aligning closely with the average found across a diverse range of Arabica samples from different countries and botanical varieties. Interestingly, in addition to caffeine, researchers identified the presence of theacrine—an alkaloid previously undetected in any other coffee beans, regardless of species.

While theacrine has not been studied as extensively as caffeine, it is known to enhance cognitive performance without inducing addiction. Some studies also suggest it has calming and even hypnotic effects. Due to its likely lower solubility compared to caffeine, the amount extracted into a brewed infusion may vary depending on extraction time. Although theacrine has never been reported in coffee beans before, it has been found in certain tea varieties and in the leaves of C. liberica, among others.

Sensory Characteristics and Market Potential

“The common perception for paramount coffee quality is that it should be Arabica, grown on farms at high elevations, which experience cool-tropical temperatures with a wide diurnal variation (i.e., considerable difference between day and night temperatures), and high UV levels. Thus, stenophylla breaks the orthodoxy for fundamental quality coffee requirements.”

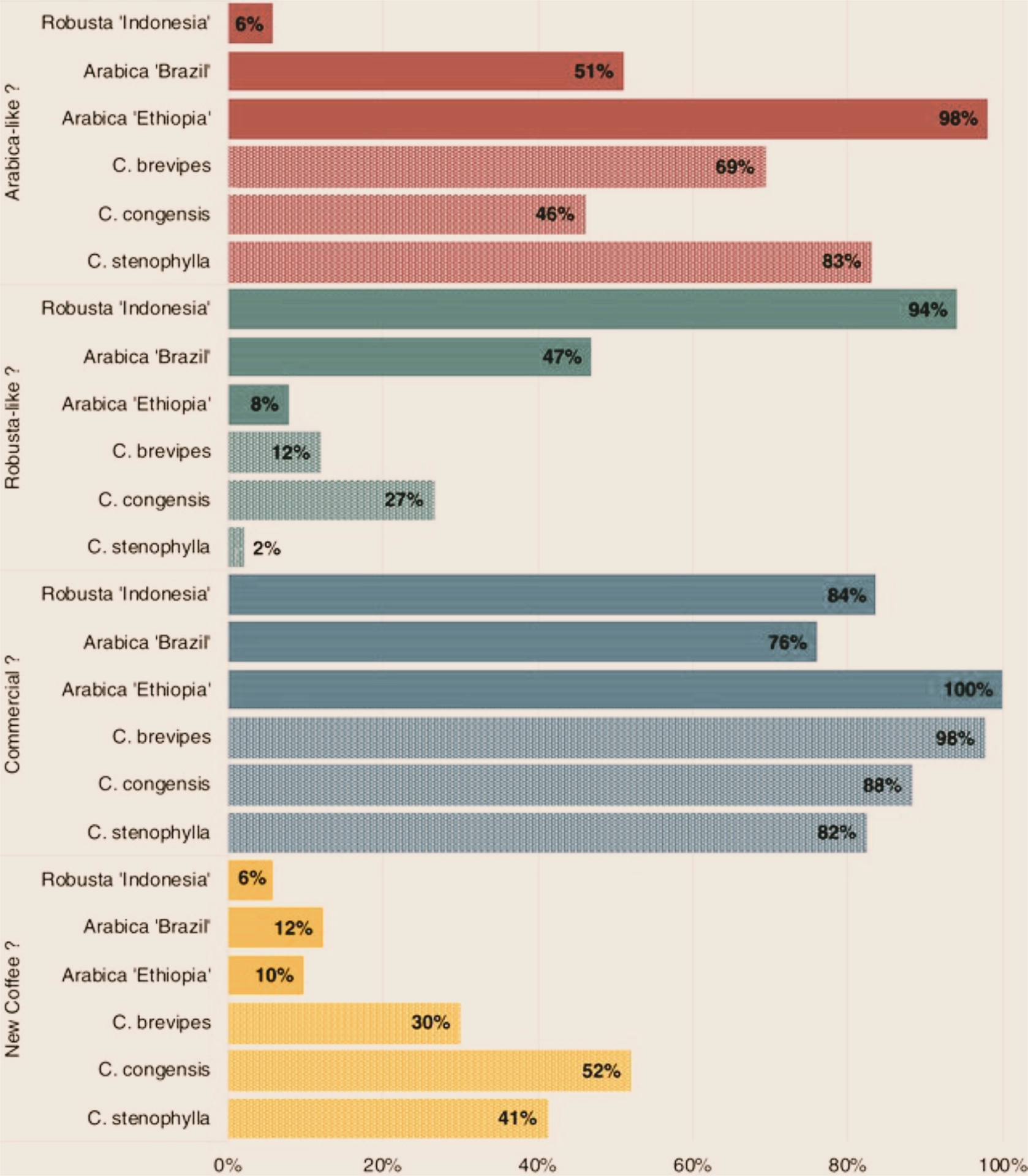

One of the most compelling reasons to explore C. stenophylla is its exceptional flavor. In a study led by Aaron P. Davis at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew, sensory panels found C. stenophylla to be “indistinguishable” from high-quality Arabica coffees, particularly Bourbon varieties from Rwanda. These findings challenge the long-held assumption that only high-elevation Arabica produces the best flavor.

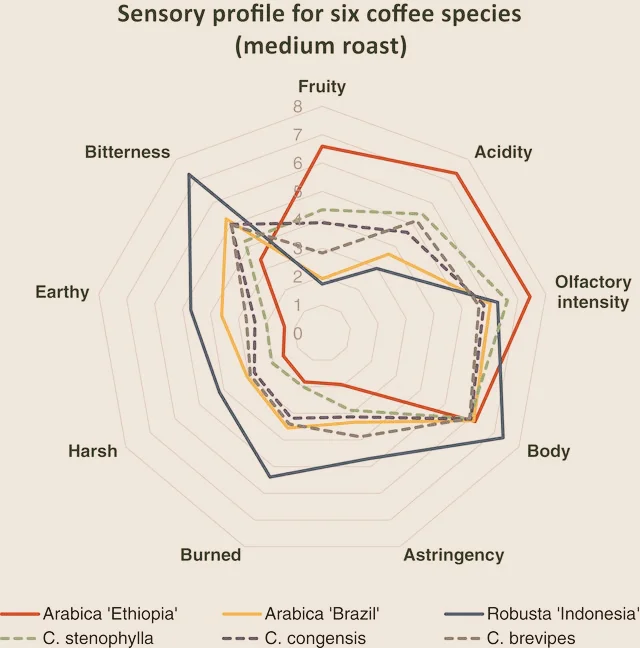

A 2021 sensory study by expert tasters highlighted that C. stenophylla exhibits:

A complex aroma profile similar to Arabica.

Balanced acidity with pronounced fruit-forward characteristics.

A flavor profile comparable to Rwandan Bourbon Arabica.

Given these results, C. stenophylla presents a promising alternative—or even a successor—to Arabica, offering greater climate resilience while maintaining high quality. Its unique combination of flavor and adaptability makes it an attractive option for specialty coffee consumers and producers seeking sustainable solutions in an evolving market.

The Importance of Recent Studies

In recent years, since 2019, practical activities have been intensified. The first cultivation of this species is being implemented, research and analysis are continuing, and scientists, with the support of the local community and foreign partners, are working to increase its protection against environmental factors, but also against uncontrolled “injection” into the current coffee market.

The good news is that thanks to PCA analysis, we know that C. stenophylla is distinguishable from Arabica and Canpehora. The comparison using metabolomic analysis based on the chemistry of green beans is important in the development of hybrid species, but also helps prevent the potential spread of “fake Stenophylla” (as a niche product with a high price) in the coffee market.

Thanks to field and genetic research, it is clear that this species is threatened with extinction. Scientists, who have discovered a correlation between the declining natural population of C. stenophylla and previous climate change and human activity, are calling for it to be protected immediately and its samples to be placed in a gene bank.

Important to emphasize: the results of sensory panels (in accordance with industry standards) analyzing C. stenophylla are the first descriptions of its taste and, at the same time, the potential it holds in more than 100 years. Yes, because humanity has known about this coffee for a long time, it's just that it has been forgotten for a long time.

Finally We Rediscovered the Treasure?

Historical records trace knowledge of C. stenophylla back to 1794. It was formally described in 1834, with samples reaching Kew Gardens (UK) by 1856. By 1904, it was not only cultivated in Sierra Leone but also in Guinea and Côte d'Ivoire. Commercially known as the 'Highland Coffee of Sierra Leone,' it was exported to France, and by 1894, colonial influence had spread its seedlings to India, Sri Lanka, Trinidad, Java, and Vietnam. Annual exports from West Africa ranged between 3 to 5 tons, making it a significant part of Sierra Leone's agriculture until the 1920s. However, with the coffee price crisis, its cultivation gradually declined. Despite being regarded as an exquisite coffee—'Suivant beaucoup de dégustateurs, c'est un café exquis'—it lost ground to higher-yielding species like C. canephora and faded into obscurity.

In the 1980s, C. stenophylla was briefly noted in field research, surviving primarily in home gardens. Forgotten by the global coffee community for decades, it remained on the fringes of cultivation—until its remarkable rediscovery just a few years ago.

One challenge is that C. stenophylla’s native population exists in a country that has never been a major coffee producer. Sierra Leone has a long but turbulent history in coffee cultivation. While production once peaked at around 20,000 tons per year more than half a century ago, it remained relatively small on a global scale. By 2023, production had plummeted to just 3,600 tons (FAO data).

Among the coffee species, C. stenophylla is one of the 60% of wild coffee species currently threatened with extinction. Known populations are found in two regions, Kenema and Moyamba, with some growing near urban areas and others hidden deep within forest reserves.

Challenges and Conservation Efforts

Despite its potential, stenophylla faces significant conservation challenges. As was marked, wild populations in Sierra Leone and Guinea are declining due to deforestation, climate change, and agricultural expansion. Genetic studies have shown that stenophylla has already undergone population bottlenecks, making conservation efforts crucial.

Several initiatives, as highlighted by Victor Brown in Sprudge magazine, are underway to protect and revive C. stenophylla cultivation:

In 2020, a tree nursery for stenophylla was established in Sierra Leone with support from the German NGO WHH.

To date, over 5,000 young trees have been planted, with local communities actively involved in the effort.

Researchers are experimenting with grafting C. stenophylla onto C. dewevrei (Excelsa) rootstock to improve growth rates and yield. “We hope that the robust and deep-rooted Excelsa plant will increase growth, shorten the time from seed to first flowering, and perhaps even improve the yield of Stenophylla,” explained Dr. Aaron P. Davis.

Companies like Sucafina have invested in stenophylla cultivation and genetic preservation.

These initiatives not only focus on the development and potential of C. stenophylla as a viable coffee crop but also contribute to local community support. As a direct result, women and young people in Ngegeru have found employment, and investors have funded the construction of clean water wells and sanitation facilities

Conclusion: The Future of Stenophylla Coffee

I recently had the opportunity to explore the potential of other coffee species. Aaron P. Davis, a botanist I had the pleasure of meeting at one of the Sensory Summits, shared with me samples of green coffee from the C. racemosa species. I had the chance to roast it, conduct a sensory analysis, and personally assess its potential—something the media has been eagerly discussing as a "coffee of the future." Compared to C. stenophylla (or even Arabica), C. racemosa stands out with its tiny green beans, no larger than a peppercorn. Its flavor, however, leans towards an intensely herbal profile, more reminiscent of lower-quality coffee. This contrast makes the emerging research on C. stenophylla all the more compelling.

While it remains too early to determine whether C. stenophylla will become a commercially significant crop, its combination of heat tolerance, genetic diversity, and Arabica-like flavor positions it as an exciting candidate for future coffee production.

Ongoing research and conservation efforts will be critical in determining whether C. stenophylla can help secure the future of coffee amid climate change. Each study of species like this expands our understanding of coffee genetics and the chemical components that define flavor. It’s encouraging to see even limited yet meaningful initiatives aimed at supporting local communities, particularly in economic and sanitary aspects.

As the coffee industry grapples with environmental challenges, could C. stenophylla emerge as the better coffee of the future?

***

I’ve drawn insights for this post from the remarkable work of researchers from prestigious institutions including the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew (UK), the University of Greenwich (UK), as well as research teams from Sierra Leone, Nigeria, and the USA. These researchers have made invaluable contributions to understanding the potential of C. stenophylla and its implications for the coffee industry. I encourage you to explore their studies for further insights into this fascinating topic:

***

Comments